[Dwelling Unit]

This series documents the lives of people working abroad.

The project began with simple visits—being invited into the apartments where they live.

The project began with simple visits—being invited into the apartments where they live.

They came from different professions and backgrounds: legal advisors, corporate consultants, English teachers, embassy staff.

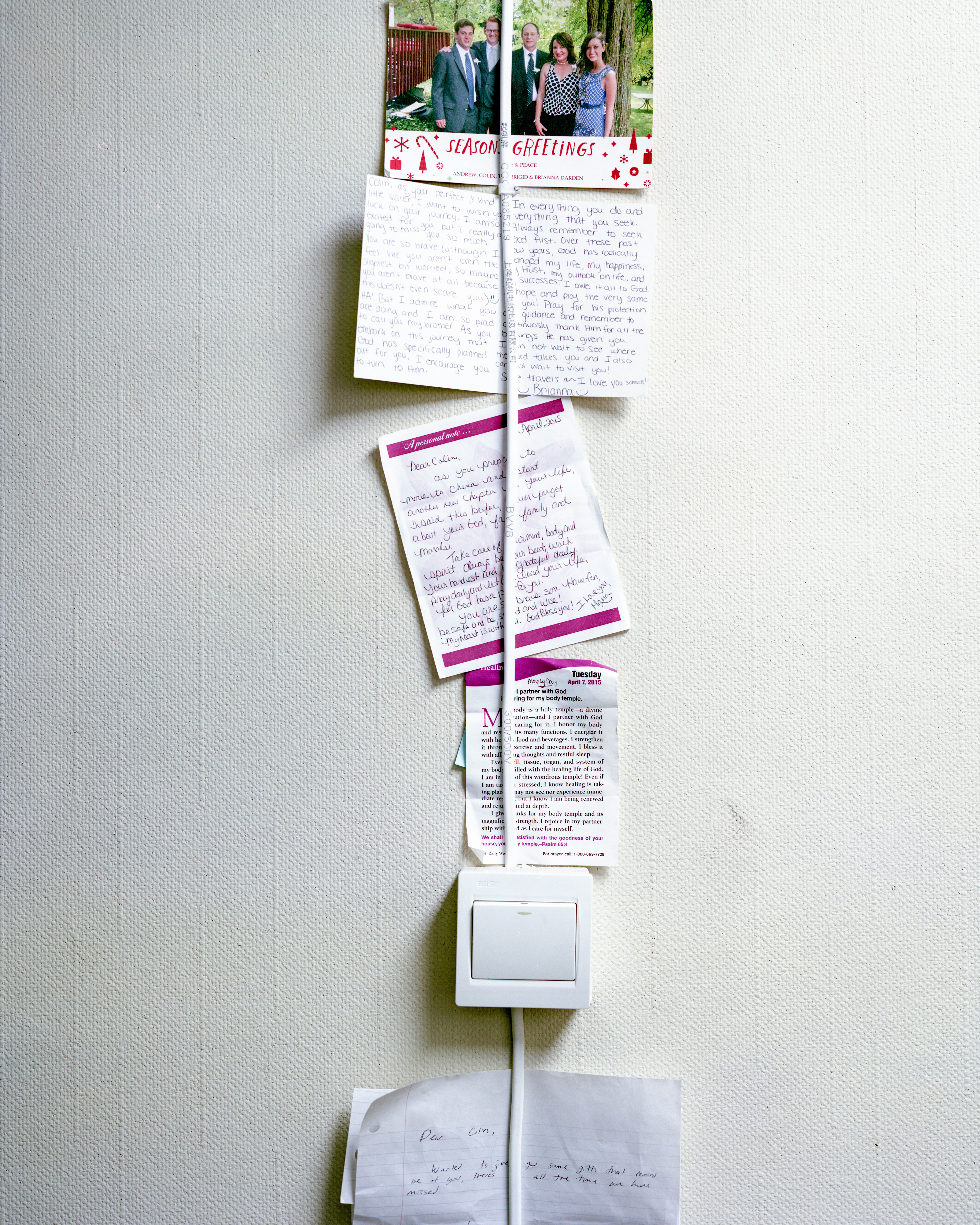

Yet despite their variety, the spaces they inhabited were remarkably minimal and quiet.

Each room was stripped down to its essentials—only what was needed for daily life remained.

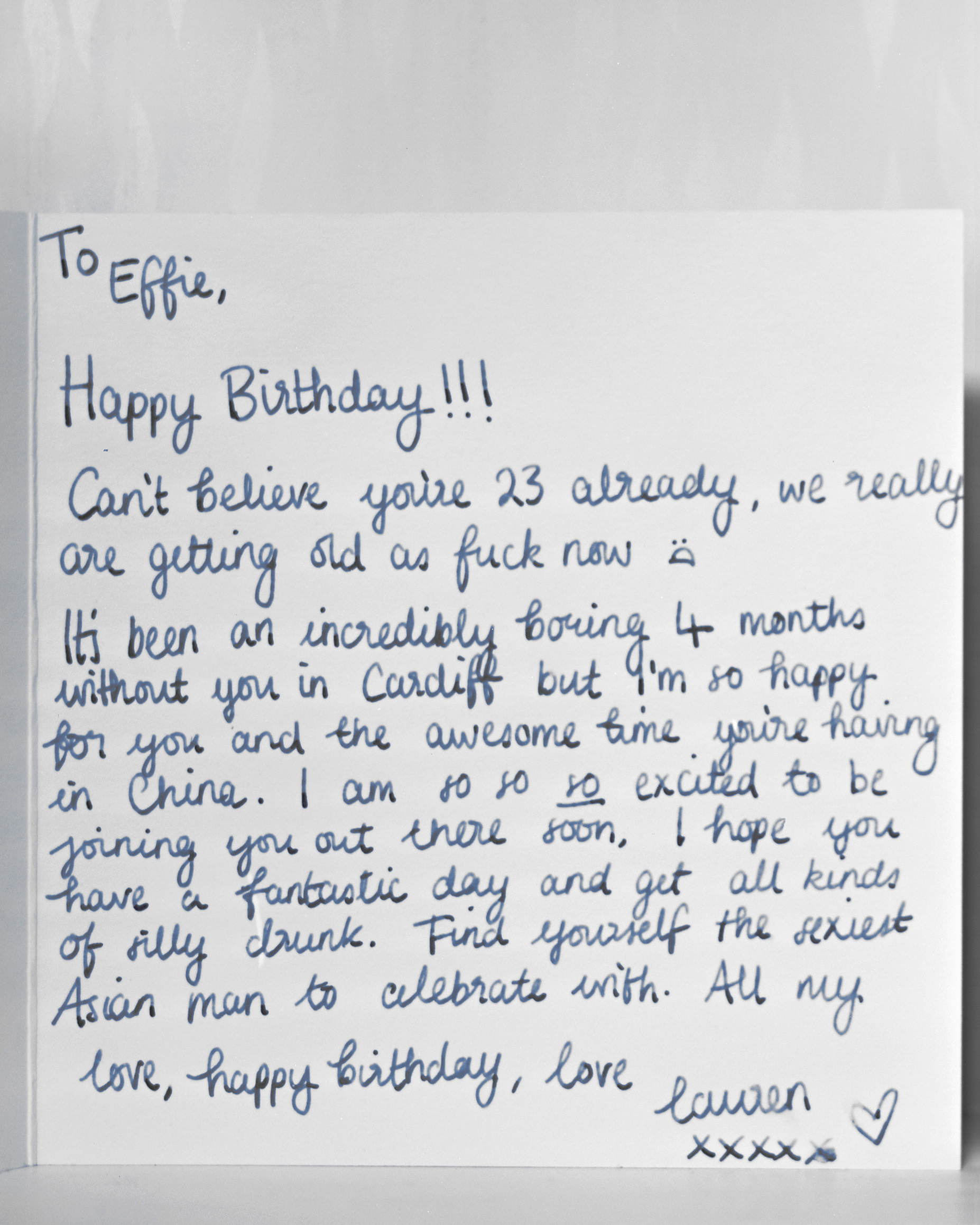

There were few decorative elements, few traces of rooted identity.

The apartments felt temporary, as though they were meant to be passed through, not lived in.

Yet despite their variety, the spaces they inhabited were remarkably minimal and quiet.

Each room was stripped down to its essentials—only what was needed for daily life remained.

There were few decorative elements, few traces of rooted identity.

The apartments felt temporary, as though they were meant to be passed through, not lived in.

Occasionally, I was invited to join their home gatherings—parties held in modest kitchens, surrounded by laughter and music.

There was a lightness in those moments, a Western-style blending of public and private spaces.

But even in those bursts of sociability, I sensed something unspoken lingering beneath—a presence of dislocation.

Perhaps it resonated so strongly because it reminded me of my own experience.

There was a lightness in those moments, a Western-style blending of public and private spaces.

But even in those bursts of sociability, I sensed something unspoken lingering beneath—a presence of dislocation.

Perhaps it resonated so strongly because it reminded me of my own experience.

When I first arrived in Japan, I lived in a one-room apartment owned by Leopalace.

It was 16 square meters—barely enough space for a bed, which took up most of the room.

The living area was swallowed by that bed, and I began to feel like an afterthought in my own life.

Surrounded by unfamiliar language, customs, and systems, I gradually felt my sense of self fading into the background.

It was 16 square meters—barely enough space for a bed, which took up most of the room.

The living area was swallowed by that bed, and I began to feel like an afterthought in my own life.

Surrounded by unfamiliar language, customs, and systems, I gradually felt my sense of self fading into the background.

But then, one Sunday morning, something shifted.

I happened to glance out the western window and saw Mount Fuji—

perfectly framed within the edges of the window like a painting.

I happened to glance out the western window and saw Mount Fuji—

perfectly framed within the edges of the window like a painting.

Nothing in the room had changed.

It was still quiet, still small, still solitary.

But in that moment, something in me reconnected.

The body and the landscape, once estranged, recognized each other again.

It was still quiet, still small, still solitary.

But in that moment, something in me reconnected.

The body and the landscape, once estranged, recognized each other again.

The people I photographed are living in foreign places,

but they also reflect something of my own displacement.

When you live in a space that feels provisional,

you become more alert to what can’t be spoken.

The absence of permanence sharpens your ability to see, to feel.

but they also reflect something of my own displacement.

When you live in a space that feels provisional,

you become more alert to what can’t be spoken.

The absence of permanence sharpens your ability to see, to feel.

Just as I once glimpsed Mount Fuji through a narrow window and felt unexpectedly whole,

I see in these minimal rooms a kind of quiet resistance—

a way of rebuilding meaning in the absence of place.

I see in these minimal rooms a kind of quiet resistance—

a way of rebuilding meaning in the absence of place.

This project is not about decoration, but function.

Not about eloquence, but silence.

It is about how a person’s relationship with the world is not always shaped by identity or narrative,

but sometimes, simply by the window through which they see.

Not about eloquence, but silence.

It is about how a person’s relationship with the world is not always shaped by identity or narrative,

but sometimes, simply by the window through which they see.

この作品は異国で働く人々の暮らしを断片的に撮影したものである。

撮影は、彼らの実際の住まいに足を踏み入れるところから始まった。

撮影は、彼らの実際の住まいに足を踏み入れるところから始まった。

法律顧問、企業コンサルタント、英語教師、大使館職員――職業も国籍もさまざまだが、

彼らが住まうアパートの内部は、驚くほど簡素で静かだった。

生活に必要なものだけが最低限に置かれた空間。

そこには物語の装飾や趣味的なものは少なく、

機能としての「住まい」が、どこか一時的な仮の姿として横たわっていた。

彼らが住まうアパートの内部は、驚くほど簡素で静かだった。

生活に必要なものだけが最低限に置かれた空間。

そこには物語の装飾や趣味的なものは少なく、

機能としての「住まい」が、どこか一時的な仮の姿として横たわっていた。

部屋の中で撮影していると、ときおり「ホームパーティー」に誘われることもあった。

気さくに人を招き、食卓を囲み、陽気な音楽とともに笑い合う様子は、

西洋的なパブリックとプライベートの曖昧な交錯を感じさせる。

だが、その賑やかさの背後にも、どこか「定着しない身体」の気配が残っているように思えた。

それはたぶん、私自身の記憶と重なっていたからだろう。

気さくに人を招き、食卓を囲み、陽気な音楽とともに笑い合う様子は、

西洋的なパブリックとプライベートの曖昧な交錯を感じさせる。

だが、その賑やかさの背後にも、どこか「定着しない身体」の気配が残っているように思えた。

それはたぶん、私自身の記憶と重なっていたからだろう。

初めて日本に来たとき、私はレオパレスのワンルームに暮らしていた。

16平方メートルの空間。

リビングはほとんどベッドだけで埋まり、自分がこの部屋の「余白」になったような気がした。

知らない言語、知らない土地、知らないルールに囲まれ、

私の輪郭はだんだんと薄くなっていった。

16平方メートルの空間。

リビングはほとんどベッドだけで埋まり、自分がこの部屋の「余白」になったような気がした。

知らない言語、知らない土地、知らないルールに囲まれ、

私の輪郭はだんだんと薄くなっていった。

けれど、ある日曜日の朝のこと。

ふと西の窓を覗くと、そこに富士山があった。

ちょうど窓枠にすっぽりと収まるその姿に、私は息を呑んだ。

ふと西の窓を覗くと、そこに富士山があった。

ちょうど窓枠にすっぽりと収まるその姿に、私は息を呑んだ。

部屋は何も変わっていない。

狭くて、静かで、誰とも話していない空間だった。

けれどその一瞬、私の中の「風景」と「身体」が再接続されたのだった。

狭くて、静かで、誰とも話していない空間だった。

けれどその一瞬、私の中の「風景」と「身体」が再接続されたのだった。

この作品に写っているのは、異国に身を置く人々の生活風景だが、

それは同時に、かつての私自身を写し出す鏡でもある。

不確かで一時的な空間に身を置くことで、

人はむしろ「見ること」と「感じること」の感度を高める。

それが、まるで窓越しに富士山を見たときのような、

不意に訪れる象徴との邂逅を可能にする。

それは同時に、かつての私自身を写し出す鏡でもある。

不確かで一時的な空間に身を置くことで、

人はむしろ「見ること」と「感じること」の感度を高める。

それが、まるで窓越しに富士山を見たときのような、

不意に訪れる象徴との邂逅を可能にする。

このシリーズは、「場所を失った身体が、どのように意味を再構築するか」

という問いの上に成り立っている。

そこにあるのは、装飾ではなく機能、饒舌ではなく沈黙、

そして、言葉の手前で立ち上がる、風景との関係である。

という問いの上に成り立っている。

そこにあるのは、装飾ではなく機能、饒舌ではなく沈黙、

そして、言葉の手前で立ち上がる、風景との関係である。

ひb